Their trials and tribulations

On Serbia’s Bunjevac

The Bunjevac community's identity has been pilloried from generation to generation, including a 1945 instruction to treat them as Croatians. The so-called ‘Bunjevac question’ remains a source of considerable conjecture; a conjecture that is in the shrewd and determined hands of the Bunjevac National Minority Council in Serbia.

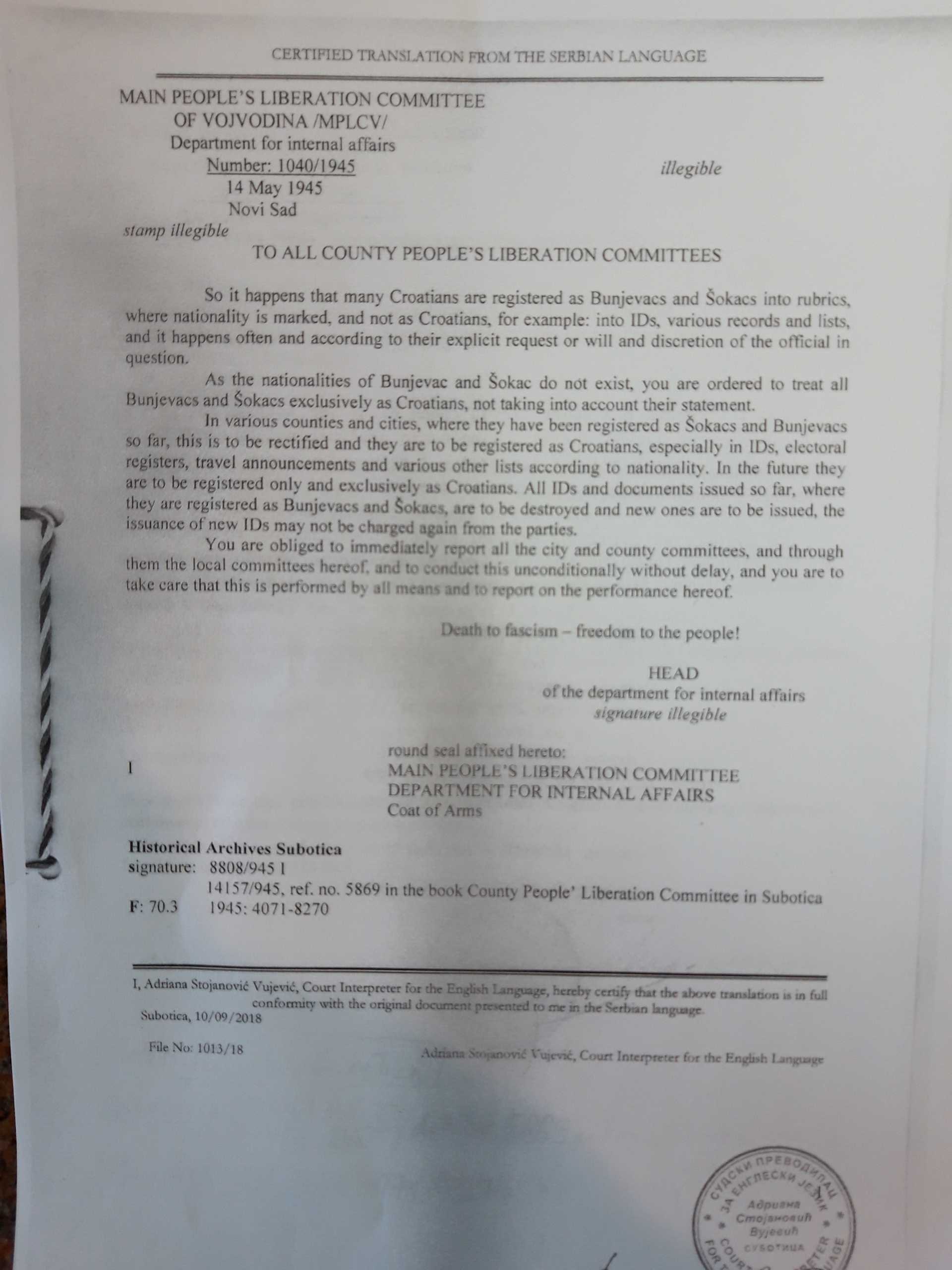

With his hooked nose, croissant-shaped moustache balanced on his upper lip, and hair receding to both sides, Mirko Bajić reaches across the table to hand me a document from the Historical Archives in Subotica. The first thing I notice is the date - 14th May 1945 - only a month after the liberation of Yugoslavia from the Nazis and their collaborators after several years of devastating war. The second is the closing, ‘Death to fascism - freedom to the people!’ (‘Smrt fašizmu, sloboda narodu!’); words which, though still occasionally uttered today (though often nostalgically), would have had a particular resonance amidst the ruins of war. I can feel the glare of Bajić’s gaze as I read on, or indeed from the beginning, ever more conscious of my facial expressions and concerned about any perceived lack of sincerity or sarcasm. For this is no laughing matter, certainly not for the head of the executive board of the Bunjevac National Minority Council in Serbia; proudly representing a community more frequently associated with the lyrics of Zvonimir ‘Zvonko’ Bogdan (who also gives his name to a very good vineyard just outside Subotica).

The paper is a certified copy of an instruction from the Main People's Liberation Committee of Vojvodina and addressed ‘To All County People's Liberation Committees’. It states that ‘as the nationalities of Bunjevac and Šokac do not exist, you are ordered to treat all Bunjevacs and Šokacs as Croatians’ (the term ‘Croatians’ is used in the translation rather than ‘Croats’). It demands the destruction of all IDs and documents where individuals are registered as one of these two nationalities, and for members of each community to instead be registered as Croatians, ‘especially in IDs, electoral registers, travel announcements and various other lists according to nationality’. It tasks all city, county, and local committees to ‘conduct this unconditionally without delay’ and report back henceforth. It is drafted in the crisp, dry language of bureaucracy; a language that can condemn identities, and sometimes individuals, to administrative erasure in the space of a few short, sharp sentences and paragraphs. Its content is such that one has been tempted to have it framed and hung in the corridor, where it can serve as a daily reminder of the ease with which terms of erasure can be signed and stamped.

Yet this is no historical relic, though very few of those alive when the instruction was published are with us today. For Bajić, this document constitutes an act of ‘violent assimilation’; one which reverberates now and in the future. He is steadfast in his demand that these decrees be not only revoked but denounced. Though it may sound trivial to the uninitiated, it goes to the heart of the existential angst that grips the Bunjevac community. Though they are understood to have migrated here from Dalmatia (in nearby Szeged in Hungary, they were referred to as ‘Dalmát’ or ‘Dalmatians’, and to this day are not recognised as Bunjevac but instead treated as part of the Croatian community) and Herzegovina in the late seventeenth century - 1686 is celebrated as the year of the migration - the Bunjevac here in Vojvodina are proud to declare Serbia as their homeland. Though mainly Roman Catholic, they repeatedly insist that they are not part of the Croat minority. A statement issued by the Alliance of the Bačka Bunjevci, a political party, claims that ‘even today, those who represent the Croat minority in the Republic of Serbia - and who remain silent in the face of the return of Ustašism in Croatia - represent us Bunjevci as Croats, taking away our language, culture, and traditions, refer to us as “Bunjevci Croats” - while the state watches this in silence’.

Up until 1991 both the Bunjevci and Šokci - as they are known in their plural form - were ‘shown collectively with the Croats’. Bajić wonders out loud what the true number of Bunjevci would be today had their identity not been conflated with that of Serbia’s Croats; if their children and children’s children, for he is a man of advancing years, had been imbued with simply an awareness, let alone a sense of pride, about their origins. He is an opponent of the term ‘Bunjevac Croats’, which he describes as another attempt at assimilation. The number of people who identified as Bunjevac in the last census was 16,706 (whilst the number of Šokci was 607), most of whom reside in Sombor and Subotica; a decline from 21,434 in 1991. He fears the numbers to be recorded in the census that approaches.

On the day I first met the Bunjevac National Minority Council, one of Serbia’s national newspapers, Politika, covered the dispute over the name of Bački Vinogradi (known as ‘Királyhalom’ in Hungarian), close to the border with Hungary. Subotica’s City Assembly had decreed that its name in the Croatian language would be ‘Kraljev Brig’; a decision Bajić described as an ‘extension of the provision forcing Bunjevci to declare themselves as Croats’. They instead insisted that ‘Kraljev Brijeg’ would be a more accurate rendition in the standardized form of Croatian. It may seem banal to most - one syllable or two - but for the Bunjevac community, it constitutes an affront to their identity. They have worked hard to standardize the Bunjevac language - its dictionary, grammar, and orthography - and are seeking its full incorporation into school curricula. They deem their language to be a key part of their community’s revival and believe such decisions constitute a further attempt to denounce their identity.

Suzana Kujundžić Ostojić, head of the Bunjevac National Minority Council, describes it as their ‘democratic right to identify as Bunjevci’, and speaks passionately about what she describes as an ‘autochtonous national revival’. She does so whilst seated beneath a momentous painting of the Grand National Assembly in Novi Sad, capturing the historic role the Bunjevac played in supporting the decision to join Bačka, Banat, and Baranja with the Kingdom of Serbia (subsequently the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians) after the First World War and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. On the wall hangs a rather regal-looking coat of arms, with a light blue similar to the Argentine flag. Kujundžić Ostojić refutes accusations that the community’s current standing derives from the destructive political dynamics of the nineties, which gave rise to suggestions that the Bunjevac community was favoured over Serbia’s Croats. Their struggle is not a new nor recent one, she reiterates.

As I make to leave, Bajić says to me, ‘a Bunjevac isn't a Bunjevac unless they are stubborn’. From the fifth floor of their socialist-era offices, I look out over Subotica’s art nouveau architecture and wonder whether this multi-ethnic place hadn’t softened some of that stubbornness. Yet when one’s identity has been pilloried from generation to generation, such stubbornness is indeed a virtue. Their national identity - the so-called ‘Bunjevac question’ – remains a source of considerable conjecture; a conjecture that is in shrewd and determined hands.

Ian is a writer based in the Balkans. He is the author of 'Dragon's Teeth - Tales from North Kosovo' and 'Luka'. Follow Ian on Twitter @bancroftian.

Currently in: Belgrade, Serbia — @bancroftian