Fusing art and (cold) war

Tito's secret nuclear bunker

A once secret nuclear bunker in Konjic, Bosnia-Herzegovina - built to safeguard former Yugoslav president, Josip Broz Tito, and other members of the elite - is now home to an internationally acclaimed art collection that confronts various aspects of the Cold War.

“You can tell a million stories about the Cold War”, Edo tells me in his downtown Sarajevo apartment, before proceeding to recount several of his own. Edo and Sandra Hodzic, two artists from Bosnia-Herzegovina, continue to catalyse the production of Cold War reflections.

Having transformed a once top secret nuclear bunker near the town of Konjic, they have collated works from over one hundred artists; seventy five of whom have represented their respective countries at the Venice Bienniale. It is a diverse collection, built-up over four editions of its Biennial which, unlike many of its peers, share a common theme - the Cold War. The works confront not only the military dimensions of the US-Russia stand-off, but the social, cultural, political and economic transformations which occurred during this period. As Edo notes, “artists bring stories from the real, outside world - sometime lethargic and funny, sometime prophetic and horrifying.”

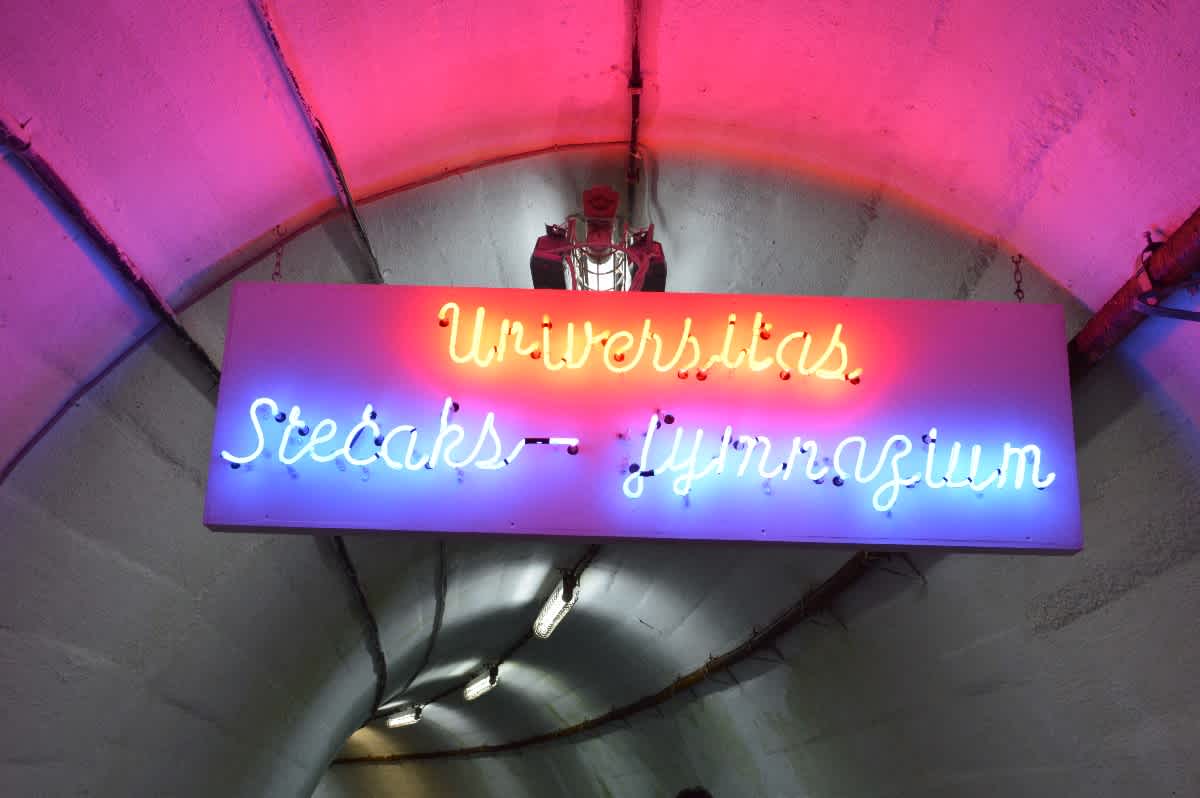

The bunker - also known as the ARK (Atomska Ratna Komanda, or Nuclear Command Bunker) - is a unique and unorthodox space. The original fixture and fittings accumulate dust amidst the hum of the original air conditioning system. In the case of emergency, the bunker was designed to be hermetically sealed in a matter of seconds. Were the bunker to be attacked, explosives were ready to sabotage vital blocks. Though both possibilities have been disabled, there is a lingering sense of foreboding.

The space is nauseating. The original wallpapers - turquoise, beige and various shades of grey - a sharp contrast to the virgin white of contemporary galleries. A former soldier leads a group of restless teenagers through the Ark’s various blocks. His deadbeat tone and demeanour are in harmony with the bunker’s atmosphere. Edo speaks about the solitude one feels upon entering; a solitude that is “so terrifying yet also, at the same time, monumental and grandiose.” He describes how upon entering, “all the artists were in shock. Noone wanted to try to beat the energy of the place.”

The space has stimulated an important fusion between art and military. Luchezar Boyadijev’s Endspiel (End game) features an elongated chessboard on which an endgame scenario for nuclear Armageddon is conceived. The late Edo Murtić in ‘Cadavers 1995/2012’ presents the luminous skeletons of generals, replete with their military regalia and decorations, glowing amidst a darkened room as one passes before the “most vocal spokesmen of death.”

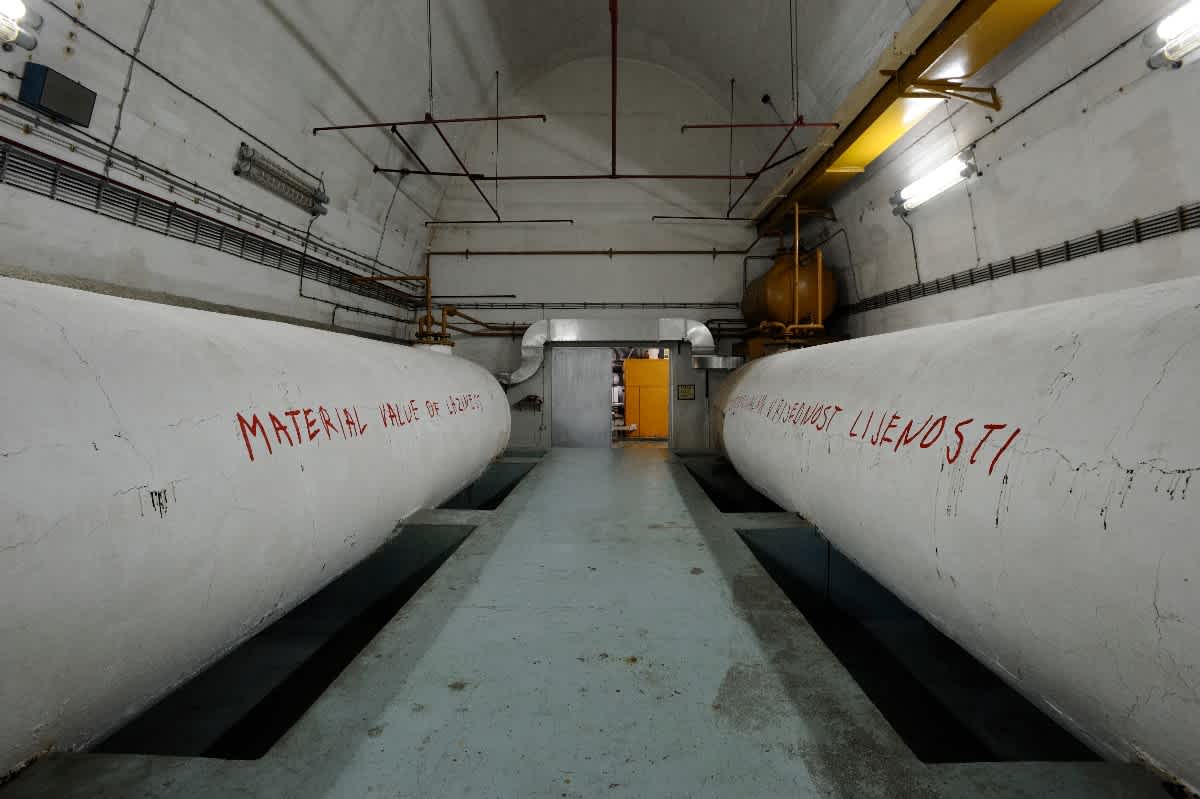

There are numerous pieces addressing the various transformations that took place during the Cold War age, each tailoured to the specifics of the bunker environment. Selma Selman’s ‘Iron Curtain/Mercedes’ challenges the ideological divides of the Iron Curtain; whilst Mladen Stilinović explored the ‘Material Value of Laziness’ with a work in which those very words are dubbed on the side of a large diesel tank in Blok of the ARK.

“The Cold War never ended,” Edo tells me, “it remains an on-ongoing process.” It never ended "because Hollywood won that game. Hollywood changed the Soviet Union. They got democracy, a way for a better life. That kind of movie. A better kitchen, car, holidays in Hawaii. But the military story is the same as in the Cold War. We still have atomic bombs.”

Edo says that Tito's name is "a minnomer...a distraction", but that "it draws people." The fifth and final Biennial in 2019 will involve one artist on from the USA and Russia, respectively. The future of the bunker itself, however, remains as uncertain as relations between these two Cold War protagonists.

Ian is a writer based in the Balkans. He is the author of 'Dragon's Teeth - Tales from North Kosovo' and 'Luka'. Follow Ian on Twitter @bancroftian.

Currently in: Belgrade, Serbia — @bancroftian