Ghosts of empire, political Islam and crumbling casbahs

Algiers’ struggle

De Gaulle may be long gone but the legacy of France's presence in Algeria doesn't just influence social and political life in Algeria - it dominates it. In Algiers alone, just miles separate conceptions of "French" modernity and shadowy dive bars from brutalist visions of Sharia law. The most impressive architecture of the city may be classically French but the ancient casbah - and its Islamic history - still just about clings to life.

The thing that has always struck me about Algeria is its simultaneous sense of closeness and distance.

Sitting in London, one is just two hours and fifteen minutes by plane - in a straight line to the south - to its capital Algiers, yet from a British perspective the country is somewhat of a mystery, with a limited shared history, entirely absent linguistic links and no substantial UK-based diaspora. Unlike Tunisia, whose sandy beaches were famed before the Arab Spring's attendant terrorist backlashes emptied out its resorts, modern British perceptions of the country are shaped chiefly by lingering memories of its bloody civil war and proximity to the perceived badlands of Libya.

Visiting the country is not an easy undertaking. Indeed, even after painstakingly obtaining the correct paperwork for the country, its UK Embassy went to great lengths to emphasise that "Algeria is a closed country" with "nothing for tourists to do". But they duly issued by visa - and my passage into the country was fairly painless, bar a flurry of questions from immigration officials at Algiers airport about my political views or any intentions I had to upload mocking YouTube videos about the country's leadership.

Driving from the airport into the heart of the city of Algiers is an exhilarating experience. The city cannot be described better than in a passage from Andrew Hussey's 'The French Infitada' which chronicles France's occupation of the country when he describes Algiers as, "like Marseilles, Barcelona, Naples or Beirut, one of the great Mediterranean cities" with the "pine forests of the surrounding hills and the magnificent dark blue sweep of the bay" gradually revealing themselves to you the closer you approach.

Indeed, it is this sense that Algiers is indeed a familiar Mediterranean city - an impression reinforced by the French architecture, ornate wrought-iron balconies and ornate garden squares - that make the numerous mosques seem out of place, when the reality is very much the other way around.

For me, the most important site in the city that I had wanted to see was the seventeenth-century casbah, a vast network of private homes and businesses which stretches up from just behind the city's harbour to the top of the hillside; revealing sparkling views of ocean below.

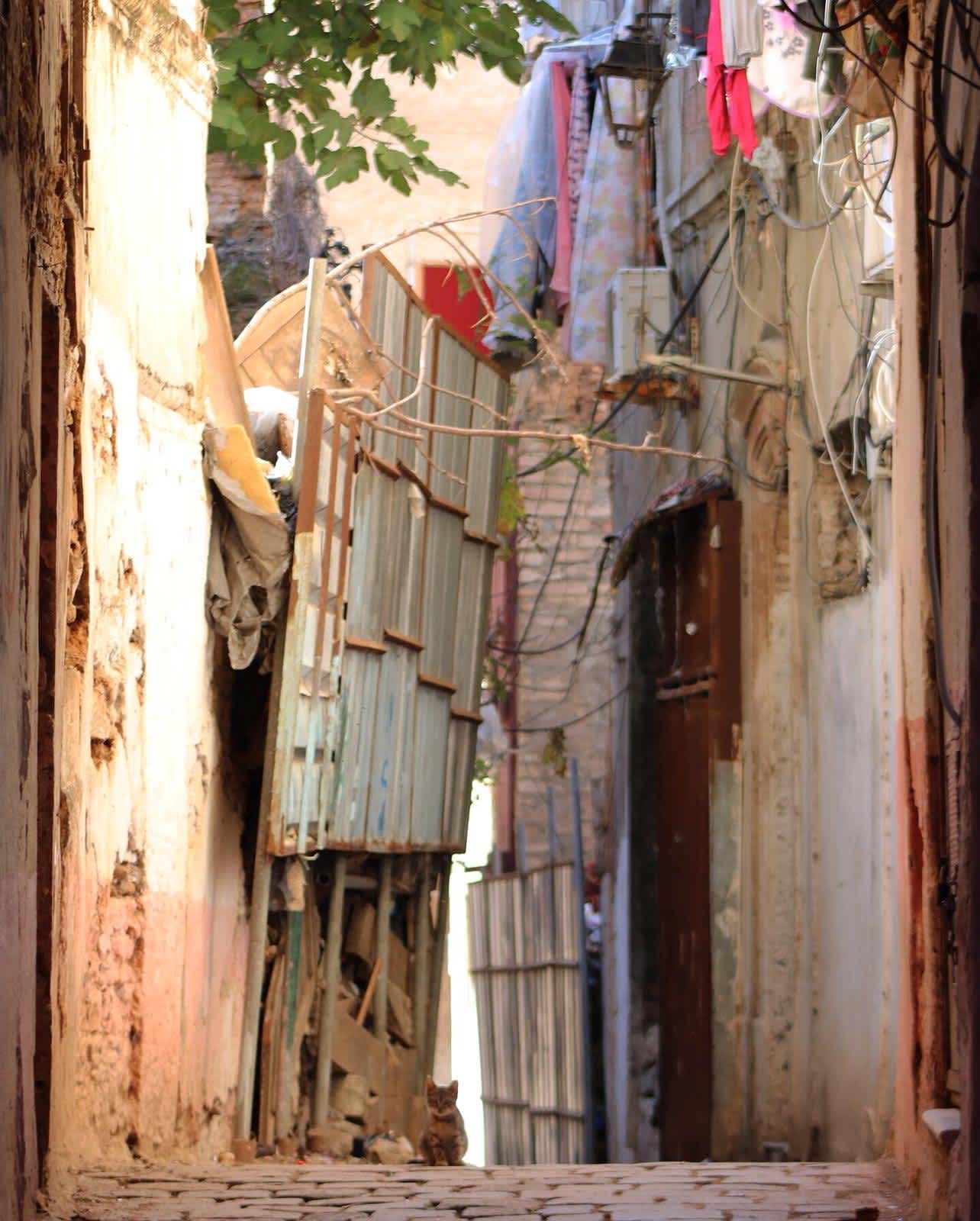

Given its history, I had hoped to experience the hubbub of mass Orientalist commerce I had seen in Tehran's Grand Bazaar, the order and dignity of the casbah of Tunis and exoticism of Cairo's Islamic district. Instead, what I found was a warren of fetid alleyways with rubbish piled high against buildings that clearly collapsed many decades ago and a sense of near-abandonment. Whatever sense of history the casbah may have had now sits under piles of rubble, with the only real places of interest to me being its small cafes which, armed with a couple of double espressos, provided venues for people-watching.

It is said that the French had wished to demolish the casbah during the occupation and that the wholly Algerian-run governments since then were of a similar view. Despite being a supposedly UNESCO-protected area, the demolition of the casbah of Algiers is not being achieved by the wrecking ball but by the forces of wind, rain and neglect. It may not be too late to rescue something of the casbah - but I fear it is.

Arguably the most impressive building I saw in the city was the Our Lady of Africa church completed in 1972 by the architect Jean-Eugène Fromageau who was responsible for the French redesign of the city and its imposing boulevards and promenades. The church, with its mosaic tiles in shades of blue and green and domed roof, could easily see if confused for a mosque - indeed, its design is far more in keeping with any conceptions of Arab architecture I had than any of the other incongruous buildings the French occupation threw up in this part of North Africa.

Inside the church and over its nave, a mosaic reads: "Notre Dame d'Afrique priez por nous et pour les Musulmans" ("Our Lady of Africa, pray for us and for the Muslims"). A more perfect encapsulation of the "them and us" attitude the predominantly Catholic French occupation - sitting in their church, high on a hill above the huddled masses below - had towards the country's indigenous majority it would be hard to find.

For me, the most interesting part of the city was the working class district of Bab El Oued.

It was here, more than anywhere the city, I actually felt a sense of proud Arab Algeria as opposed to a society trying to assert itself around the architecture - literally and figuratively - of a former colonial power. The streets were swarming with people, spice merchants plied their trade alongside show-owners hawking cheap Turkish-made prayer mats, the smell of shisha and shawarma was piquant in the area and the call to prayer sparked a meaningful response on the streets as opposed to the indifference it was met with in wealthier districts just a couple of miles away.

The outward piety of Bab El Oued made it, I must confess, an uncomfortable place to relax.

It was, after all, a bastion of Front Islamique du Salut (FIS) whose near-election win in 1991 on the back of appeals to disaffected young people and conservative working class communities saw the country explode into a protracted war against more secular, nationalist military interests. When compared to more affluent areas of the city, the quota of men wearing beards and women dressed in veils was pronounced, with the Arabic language being the order of the day.

Walking through the area, the mixture of judicious looks I attracted from passing pedestrians and occasional graffitied FIS slogans on buildings compounded this sense of unease. Bab El Oued is scarcely a place secular Algerians visit, let alone a welcoming venue for gawping tourists.

The centre of the city, particularly the main Didouche Mourad Street, made for far more comfortable territory - at least from the perspective of a western visitor. Didouche Mourad is lined with the same shops and cafes one would reasonably expect from any well-heeled European capital, from designer handbag stores to luxury florists. It is, therefore, fairly unremarkable - albeit it serves as the heart of secular Algiers.

By day, the main boulevards of central Algiers are choked by dawdling people and slow-moving traffic but, as soon as dusk falls, the city seems to empty as residents retreat indoors and shutters come down over businesses. For anyone unfamiliar with the city and staying in the roads leading off the central drag, the area can feel rather post-apocalyptic by night.

Prior to the 1990s civil war, which smashed to dust any outward indications of the more secular society fostered during the French occupation, I am told the city had a fairly vibrant social scene with numerous bars and live music venues providing a comfortable haven for young people more inclined to look north to Paris than east to Mecca.

Today, the consumption of alcohol - while formally tolerated by the authorities - is very much a behind-closed-doors pursuit, both literally and figuratively. While neighbouring Tunisia's piety towards alcohol appears to extend to banning you from drinking a beer in an outdoor terrace facing the street but tolerates consuming that same beer behind the same venue's large glass windows facing that same street, Algiers' remaining drinking dens are hidden behind reinforced steel doors and starved of natural light. This is no doubt a legacy of the 90s, when such venues were presumably magnets for the worst kinds of Islamist thuggery.

I say "drinking dens" not to be pejorative but rather to be accurate. Quite by accident, I managed to find three of the remaining bars operating in the city and was, after a few unsure moments of pressing the intercom to seek entry, admitted to a series of smoke-filled caverns populated exclusively by middle-aged men puffing away on acrid cigarillos while slowly nursing stubbies of beer.

The conversation among patrons was purely in French - indicating to me that the patrons were drawn from the country's professional classes - and I overheard a few remarks about the country's looming presidential elections which appeared to confirm the counter-culture nature of the establishment. "Ben-fliiiis," one patron announced to his drinking partner with mournful sincerity when discussing the nationalist presidential candidate Ali Benflis, "est TRÈS anti-Islamist!", drawing an approving clink of a glass from his friend.

The restaurant scene was no less impregnable to outsiders; particularly those wishing to sample local red wine which was so popular internationally in the 1950s and 60s that Algeria became the world's largest alcohol exporter. Those restaurants I did find - all of which specialised in tasty lamb shank-style dishes - shared the peculiarities of the city's bars.

One such place, Le Caracoya, located on a deserted, hum-drum street close to the exit of a metro station displayed a simple brass plaque with its name on and a bell

Chancing my luck, I pushed it and was almost-immediately ushered into a small room by an elderly man with an enigmatic smile and firm handshake and led down a passage to a vast courtyard replete with an indoor fountain and seating for around 200 guests, with about half the seats taken. The place was well-maintained and had an air of faded grandeur, yet clearly hadn't been substantially upgraded since the last French battalions scurried out of Algiers in 1962. Indeed, looking as I thumbed through the menu and enjoyed a highly-agreeable glass of Koutoubia Grenache, I imagined the dining room full of well-fed French colons feasting on steaks and raising a glass to the brilliance of General De Gaulle, quite unaware of the bloodbath befalling their troops just miles outside of Algiers.

De Gaulle may be long gone but the legacy of France's presence in Algeria doesn't just influence social and political life in Algeria - it dominates it. In Algiers alone, just miles separate conceptions of "French" modernity and shadowy dive bars from brutalist visions of Sharia law. The most impressive architecture of the city may be classically French but the ancient casbah - and its Islamic history - still just about clings to life.

Just as the city of Marseille, far across the water in southern France, struggles with its identity as an ethnically divided city struggling to assimilate its large North and Sub-Saharan populations into the structures of the Fifth Republic, it appears the concept of true "Algerian-ness" has yet to be even defined.

Daniel Hamilton is Managing Director at FTI Consulting. He works and travels extensively across the Balkans and former Soviet Union.